By Paddy Shea, a 2011–12 ETA in Gwangju currently living in New York City

At Incheon Airport, I dragged my two bags inside toward the baggage counter’s whirring bustle. I muttered what I thought could be my last, “Annyeonghaseyo,” to the lady behind the Korean Air counter and flung the bags onto her scale.

She read from her screen-translation of weight to currency and said, “Oman won juseyo.” I reached in my wallet, and while God only knows the true amount of Korean currency I found inside, it was less than oman won. I had already closed my Korean bank accounts and wired money home, so at that moment I was broke. I had no phone. Remaining in Korea was not an option: I counted on my next meal coming aboard the plane or not at all.

So, I said, “Sillyehamnida,” and dragged my luggage away to a rubbish bin, where I opened the cheaper of my two suitcases and separated keepers from trash. First, I dumped everything that didn’t bring me joy: old t-shirts, socks, and Korean study guides. So too the empty bottle of North Korean plum brandy I bought at the Korean Demilitarized Zone.

I unloaded both suitcases and repacked the nicer one. Most of my belongings were strewn about three benches in the middle of Incheon Airport, with a whole suitcase in the rubbish. The toughest item to consider came from my host mother. It forced me to reconsider one of my final farewells in Korea.

She had sent me packing with a box wrapped in pristine green wrapping paper. She said, “Paddy, do not open until marriage.” I laughed and said, “Ne, gwaenchanayo.” It occurred to me I had never seen Host Mom cry until then. “Saranghaeyo, Paddy!” she said. I said, “I love you, too, Omma.”

An hour later, I weighed the bulky box’s significance. I did not know what was inside. Should I open it and see if it was worth it? Could I look any crazier if I started opening a present right now? No, I promised Host Mom I’d wait until marriage, so I did.

My mom and dad picked me up from the airport and drove me home through the swampy humidity of western Massachusetts summer. Mom made salads, and Dad grilled steak, American-style. This was our first family dinner in a year and a tribute to halcyon suppers before Mom got sick.

She cut cucumbers into skin-on slices, a quarter-inch thick, and as a boy, I fiended for the stacks prepared for salads. On specious errands I criss-crossed the kitchen, swiping two at a time. “Paddy!” she warned after one too many thefts. “Leave some for the rest of us.”

On this night, she threw open the windows and blasted Sam Cooke songs like when I was a kid. We danced the box-step to “Meet Me at Mary’s Place.” Things have changed since those days; Mom got sick when I was twelve years old. She was once a classic turn-of-the-century American housewife. She worked a job she hated at an insurance company. She critiqued my grammar and my baseball game with an expert’s eye. She snuck downstairs to do laundry and smoke cigarettes until I threw her pack out. After putting my brother, sister, and me to bed, she studied to become a teacher, and when she came home she sliced the cucumbers just the way I liked them. Mom was always doing the most.

On the eve of her earning her Master’s degree and teaching license, a blood vessel burst in her brain. I stayed at my best friend’s house while she was in the hospital. We played ping-pong for hours in his basement before my dad arrived and called me upstairs: “Paddy!”

I knew it was bad because he didn’t say anything to me when I appeared in the kitchen. He turned his back on me to lead me to the garage. A chill of loneliness and fear filled me from my toes as I followed his broad, hunched shoulders past the refrigerator out of the kitchen.

The smell of gasoline pervaded my nostrils as we stepped into the garage, and my dad turned on his heel to face me. “Oh, Paddy,” he said and pulled me into a suffocating hug. His hugs always smelled smoky and sweaty like the firehouse in which he worked. “Mom is in the hospital,” he said. “She’s going to have surgery tonight.”

“Is she going to be OK?” I breathed into his shoulder. He squeezed harder, so I could feel my ribs and lungs individually.

“The doctors,” he said, and then he choked on a sob. He whispered: “She has a 50-50 chance.”

“What should I do?”

“Stay here, I’ll let you know.”

The surgeons saved her life, but she was changed. The acidity of our blood is enough to kill our brain cells, so each passing moment cost her dearly. The woman who came home from the hospital was not the same as the one I remember, who scolded me for cucumber-slice thievery. She was slowed, mentally and physically.

Shortly after she came home, my friends and I had gone around bush-lofting, or leaping into the bushes and shrubbery in our neighbors’ yards for fun. When our neighbors saw us flying headlong into their greenery, they called our parents.

My best friend’s mom screamed in our faces, and the walk home was the longest of my life. I knew my parents knew what I had done, how I had embarrassed them. But my mom only had a vacant, anti-depressed look. “I am very disappointed in you,” she said, and my heart broke.

This was how I knew she was different, that she had been discharged from the hospital but not fixed. The English language lacks vocabulary for this problem. When a body dies, we have funerals and burials; for the dead we have odes, dirges, and elegies. But when part of a person disappears, and the corporeal body remains, we are left dumb.

Los desaparecidos—“the disappeared” in Spanish—comes to mind, but that typically refers to whole people who have been lost to unknown villains. When I learned the Korean word han, I thought of wishing my mom would scream at me. Han is a repressed despair buttressed by helplessness; one suffers han when one lacks agency to keep the cruel world at bay. It’s knowing that, in the end, the world will break your heart.

Han reflects spirit-loss, and it helps answer the question whether our body and soul are one, or if it is possible to lose one before the other. My mother lost part of her spirit that summer, and nobody seemed to know what to do about it.

I landed in Gwangju to another family of educators: Host Father, Host Mom, and Host Bro. At our first family dinner, we made stilted conversation. As she spoke, Host Mom watched my chopstick habits carefully: her eyes followed my chopsticks from plate to banchan without disapproval. I gobbled some rice and—out of politeness—at least one square of spicy, fermented cabbage at each sitting: morning, noon, and night.

Kimchi is another thing entirely at 6:30 a.m. Many Koreans, including my host-family, do not distinguish among breakfast, lunch, and dinner foods. Never have I ever craved cereal as when I lived in Korea, but I quickly warmed to the array of bean sprouts, desiccated fish, and marinated meats served by Omma. Hers was the healthiest diet I ever enjoyed.

Meals were host family affairs. Like the Massachusetts Sheas, the Korean Parks always left a ballgame on the television: I quickly learned to cheer for the glory of the KIA Tigers as well as Choo Shinsoo of the Cleveland Indians. The ritual of sitting together at the table, of practicing formalities like “Jeongmal masisseoyo!,” and of making plans for the holidays brought us together.

At first I puzzled at Omma’s ability to prepare breakfast—bulgogi, rice, banchan such as sprouts, cucumber kimchi, and others Host Bro couldn’t even identify. She kept ungodly hours to prepare for the day: I once woke at 4:15 a.m. for a Skype job interview in New York City, and of course, Omma was already up banging pots and doing laundry. In summer, she sometimes slipped into my room to power off my oscillating fan, thus to save me from nocturnal fan death.

For five decades she lived this routine—a classic turn-of-the-century Korean housewife. She was a nurse by day. She was short, mainly from childhood malnourishment. She saw to it that her children and host-children were well-nourished. One night, Omma discussed something important with Host Bro, and I intuited they were talking about me. Chang Hyeon turned to me and said: “Paddy, maybe you will get a flu shot?”

I said, “OK. Where?”

“Maybe here.”

“In Gwangju?”

“No, my mom has it.”

We transitioned to the living room, where Host Bro got flustered as he attempted to translate his mother’s directions: “Pull down your shorts so I can stick this flu-shot needle in your ass.”

She took special pleasure in spoiling me. I was her third son, her American son, another teacher son in a family of educators. Every effort I made to launder clothes or wash dishes was rebuffed by the whole family. “Paddy, maybe you don’t.” This was as close as my host brother ever came to telling me, “No.” “Maybe you come have a fruit?”

Imagine my surprise when I returned home from school and discovered my raggedy old Converse All-Stars had been scrubbed beyond recognition and within an inch of cleanliness. Host Mom appeared from her kitchen, her eyes betraying her satisfaction at having cleaned up my dirty old shoes. I smiled and said, “Jeongmal kamsahamnida, Omma!”

“I like them dirty like that,” doesn’t translate well into Korean.

My childhood home is in disrepair, neglected since Mom got sick. So we celebrated that holiday—our first since my wife and I married—in Worcester, a central Massachusetts city.

Surrounded by Christmas detritus, Mom said, “Oh, Paddy, I think there’s one more for you.”

“Yeah?” I said and smiled at her. The last one is always a good one, and I wondered at the last time I got that treat.

“Well, do you remember the gift your Korean family got you?”

“Yes?” I lied.

“Yeah! She told you to open it when you got married.”

“Oh lord.”

“Well, I found it in the basement. I thought you’d want it now that you can open it.”

A slight tear in the corner belied its incredible journey: saved from the trash heap in Incheon, stored in Springfield for years, saved for last by another mother on Christmas in Worcester.

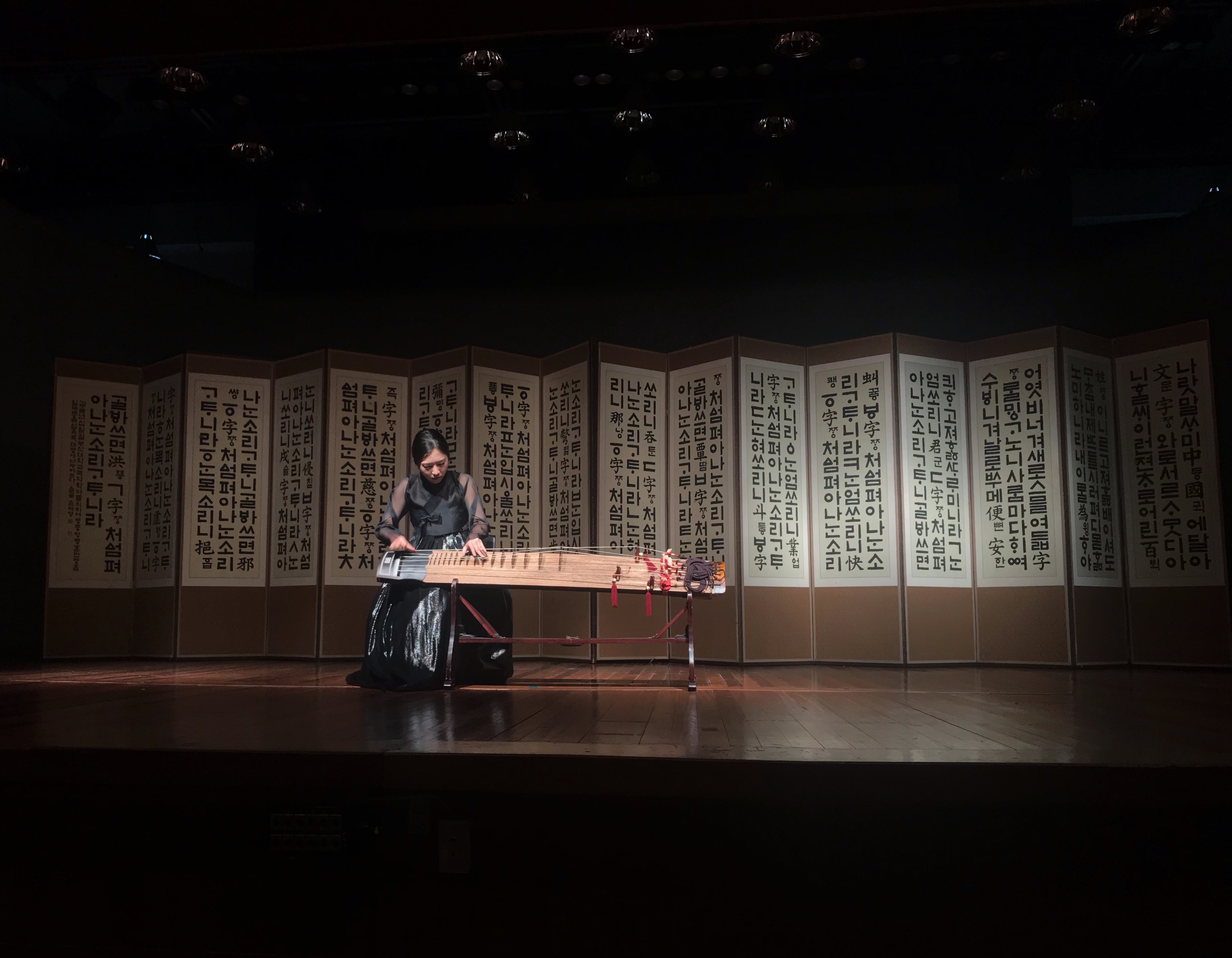

Inside: a cardboard box with red hangeul characters. Inside that: two porcelain dolls in perfect nuptial hanbok, preserved under a glass case. When I reached out to my host brother, it took months to get a response. “Hello Paddy-ssi, I am happy for you. I am married too. Merry Christmas.”

I felt the sadness of missing out when he messaged the news, but his curt response evaded the subject of my message: his mother, my host mother. I felt strange nerves as the Facetime icon blinked its rings across the globe. I smiled to myself for courage.

“Chang Hyeon!”

“Hi Paddy, how are you?” He looked exactly the same as when I left, but I recognized he was not in his parents’ apartment.

“Great! Congratulations on your marriage, man.”

“Oh, thank you.”

“So, I finally opened the gift your mom sent me home with. I waited until I got married.”

“Oh, wow.” He did not seem wowed.

“Are you at home?”

“I am at my home in Naju with my wife.”

“Gotcha. I don’t recognize the wallpaper. How are the pears?”

“Oh, very good. We eat them. Every day.”

“I bet. My buddy Jim lived and taught in Naju.”

“Yes, I remember him. He is a funny man.”

“I’ll say!” I thought again of Jim McFadden, who died in Washington, D.C. in 2013. I couldn’t speak of death on this day.

“How is your mom? Will you tell her I say ‘Jeongmal kamsahamnida’ for me?”

“Oh, Paddy,” he said. “Omma died.”

I looked at myself in the video feed, dumbstruck. I put my head in my hands, in the way I did when I learned about Jim.

“Chang Hyeon, I’m so sorry.” The tears were burning the insides of my eyes. I closed my eyelids, and the tears fell down my cheek. Never watch yourself cry on video.

“Yes, thank you.” I felt some anger that he hadn’t told me. Anger has a privilege, they say. The feeling subsided.

I thought about han, and whether our bodies and souls are permanent or permanently connected. It’s not for nothing the beautiful Korean bride on my mantle reminds me of Omma every time I see it. She is nothing but memories now, as are we all.

I recalled the last thing Omma said to me as I left her home forever: “Paddy, please do not forget us.”